7. Database Queries#

7.1. Introduction: The History of the Structured Query Language (SQL)#

The structured query language (SQL) was invented by Donald D. Chamberlin and Raymond F. Boyce in 1974. Chamberlain and Boyce were both young computer scientists working at the IBM T.J. Watson Research Center in Yorktown Heights, New York, and they met E. F. Codd at a research symposium that Codd organized there. Codd, four years prior, had published the seminal article that defined the relational model for databases. Codd’s relational model is defined using relational algebra and relational calculus, two notational standards that Codd himself created to elaborate on set theory as applied specifically to data tables. One important property of set theory is that highly abstract mathematical expressions can be expressed in plain language. For example, consider the set \(A\) of holidays in the United States during which banks are closed:

Also consider the set \(B\) of holidays in the United Kingdom during which banks are closed:

The intersection between sets \(A\) and \(B\) is a set that consists of all elements that exist with both set \(A\) and set \(B\):

The notation \(A\cap B\) is a mathematical abstraction of an idea that can be expressed in plain-spoken language: \(\cap\) means “and”, and \(A\cap B\) means \(A\) and \(B\), or all elements that are in both \(A\) and \(B\). Put another way, \(A\cap B\) is the set of all holidays during which banks are closed in both the United States and the United Kingdom. Likewise, every piece of set notation can be expressed semantically.

Although Codd laid out the broad parameters of the relational model in mathematical terms, he did not design software or a physical architecture for a relational database. He explicitly left that work up to future research:

Many questions are raised and left unanswered. For example, only a few of the more important properties of the data sublanguage … are mentioned. Neither the purely linguistic details of such a language nor the implementation problems are discussed. Nevertheless, the material presented should be adequate for experienced systems programmers to visualize several approaches (p. 387).

Chamberlin and Boyce took up the challenge of writing a programming language to implement Codd’s relational model. As Chamberlin explains, their primary goal was to create a version of Codd’s set-theoretical relational model that could be expressed in plain language:

The more difficult barrier was at the semantic level. The basic concepts of Codd’s languages were adapted from set theory and symbolic logic. This was natural given Codd’s background as a mathematician, but Ray and I hoped to design a relational language based on concepts that would be familiar to a wider population of users (p. 78).

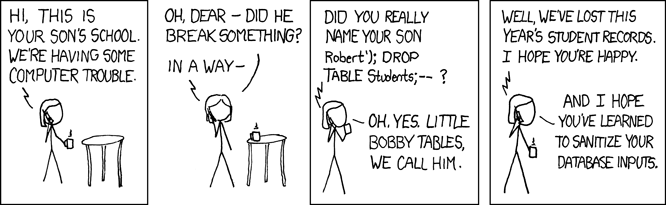

In short, the idea behind SQL is to implement Codd’s abstract system of using logical statements with set theoretical notation to narrow down the specific records and features in a dataset that a user wishes to read or edit, but to phrase these operations in accessable, plain language. One of the best things about SQL is that once you are used to the language, it reads just like English. That said, Chamberlin admits that SQL “has not proved to be as accessible to untrained users as Ray and I originally hoped” (p. 81).

Another benefit of SQL is that this language is one of the most universal programming languages in existence. It is designed to work with database management systems on any platform, and it works seamlessly within Python, R, C, Java, Javascript, and so on. While the standards for languages and platforms change, SQL has been in continuous use for relational database management since the 1980s and shows no sign of becoming antiquated or being replaced. The SQL syntax exists outside of any individual DBMS, and is maintained by the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), two non-profit organizations that facilitate the development of voluntary consensus standards for things like programming languages and hardware. Despite the universality of SQL, however, different DBMSs use slightly different versions of SQL, adding some unique functionality in some cases, and failing to implement the entire SQL standard in others. MySQL for example lacks the ability to perform a full join. PostgreSQL distinguishes itself from other RDBMSs by striving to implement as much of the global SQL standard as possible. While there some important differences in the version of SQL used by different DBMSs, the differences generally apply to very specific situations and all implementations of SQL use mostly the same syntax and can do mostly the same work.

7.1.1. Declarative and Procedural Languages#

SQL is considered to be a declarative language, which means that it defines the broad task that a particular computer system must carry out, but it does not define the mechanism through which the system completes the task. For example, SQL can tell a system to access two tables and join them together, but that command must tell a DBMS to access additional code that tells the system how exactly to search and operate on the rows and columns of each data table. A language that provides specific instructions to a system on how to carry out a task - by changing the system state in some way, including how the data exist in the system - is a procedural language. The code that a procedural language uses to make these changes on the system is called imperative code. A DBMS can be thought of as a function that takes declarative SQL code as an input, finds and runs the imperative code that carries out the declarative task, and returns the output. MySQL, for example, uses imperative C and C++ code to carry out SQL queries.

7.1.2. Popularity of SQL#

Common standards and the most popular programming languages and environments change all the time. It’s an eternal struggle for data scientists as well as programmers of all kinds, and a matter of consistent anxiety. Presently, Python is the most widely used tool for data science, but will we all have to drop Python soon and teach ourselves Julia?

In this context, it is stunning that SQL has been so widely used since the 1970s. According to a Stack Overflow survey, SQL is the one of most widely used programming languages among the people who filled out the survey, behind only to Javascript and Python. Taking into account the high-tech biases in this specific sample, it is probably the case the SQL is more widely used than any other language mentioned in this survey. What accounts for this popularity?

This blog post argues that SQL achieved this level of longevity because it came to prominence during a time in which many of the baseline standards for the development of computer systems were being invented. As more and more systems were developed in a way that depends on SQL, it became harder to change this standard. But SQL is also simple and highly functional because it is a semantic language that expresses set-theoetical and logical operations. As long as relational databases are used, there’s not much functionality that can be added to a query language beyond these foundational mathematical operations, and whatever additional functionality is needed can be added to a version of SQL by a particular DBMS. There are also many different open source and proprietary DBMSs that all employ SQL, so different users can have a choice over many different DBMSs and platforms without having to learn a query language other than SQL.

That said, there’s much less of a reason to use SQL when the database is not organized according to the relational model. NoSQL databases have much more flexible schema in general, and can store the data in one big table or in as many tables as there are records, or even datapoints, in the database. In fact, without a relational schema, the notion of a data table makes less sense in general. For example, a document store is a collection of individual records encoded using JSON or XML, and not as tables. These records can be sharded: stored in many corresponding servers in a distributed system to address challenges with the size of the database and the speed with which database transactions are conducted. Without tables, NoSQL DBMSs do not usually use SQL. MongoDB, for example, works with queries that are themselves in JSON format.

7.2. Create, Read, Update, and Delete (CRUD) Operations#

Persistent storage refers to a system in which data outlives the process that created it. When you work with software that allows you to save a file, the file is stored in persistent storage because it still exists even after you close the software application. Hard drives are examples of persistent storage, as are local and remote servers that store databases. Any persistent storage mechanism must have methods for creating, reading (or loading), updating (or editing), and deleting the data in that storage device. Create, Read, Update, and Delete are the CRUD Operations.

We’ve previously employed CRUD operations using the requests library to use an API or to do web scraping. Like requests, SQL and other query languages have CRUD operations. The following table, adapted from a similar one that appears on the Wikipedia page for the CRUD operations, shows these operations in the requests package, SQL, and the MongoDB query language:

Operation |

|

SQL |

MongoDB |

|---|---|---|---|

Create |

|

|

|

Read |

|

|

|

Update |

|

|

|

Delete |

|

|

|

As a data scientist, you will most often use read operations to obtain the data you need for your analysis. However, if you are collecting original data for your project, the create, update, and delete operations become much more important. We will discuss all four operations and their variants in the context of SQL and MongoDB below.

We can work with SQL using pandas if we first create an engine that links to a specific DBMS, server, and database with create_engine from sqlalchemy. Once we do, the pd.read_sql_query() function makes read operations straightforward, and the .execute() method applied to the engine lets us easily issue create, update, and delete commands.

7.3. SQL Style: Capitalization, Quotes, New Lines, Indentation#

There are many ways to write an SQL query, and when you look at someone else’s SQL code you will see a variety of styles. Mostly, with the exception of quotes in some cases, stylistic differences don’t change the behavior of the code, but they can have an impact on how easy the code is for other people to read and understand.

Some database systems (though not the SQL methods included with pandas) require that the SQL code for one query must end with a semi-colon, and that no semi-colons appear elsewhere in the query. As long as that requirement is met, other stylistic choices are possible.

The least readable way to write an SQL query is to write the entire code on one line, with no capitalization or indentation. The following code is valid SQL code:

select t.id, t.column1, t.column2, t.column3, r.column4 from table1 t inner join table2 r on t.id = r.id where column1>100 order by column2 desc;

We will discuss exactly what this query does. But for now, let’s focus on the presentation of code. SQL uses clauses to represent particular functions for reading and writing data. In the above query, select, from, inner join, on, where, and order by are all clauses, and desc is an option applied to the order by clause.

One stylistic choice many people make is to write SQL clauses in capital letters. That helps readers to quickly see the parts of the code that are clauses as opposed to the rest of the code that contains column names, table names, values, and aliases. If we capitalize the clauses and options in the SQL query, it looks like this:

SELECT t.id, t.column1, t.column2, t.column3, r.column4 FROM table1 t INNER JOIN table2 r ON t.id = r.id WHERE column1>100 ORDER BY column2 DESC;

Another stylistic choice people make to present the code in a more reabable way is to put clauses on new lines (except for DESC which tells ORDER BY to sort rows in descending order, and is not considered to be a separate clause from ORDER BY), so that the query looks like this:

SELECT t.id, t.column1, t.column2, t.column3, r.column4

FROM table1 t

INNER JOIN table2 r

ON t.id = r.id

WHERE column1>100

ORDER BY column2 DESC;

Some clauses are considered to be elaborations upon a previous clause. Column names after SELECT are usually written on the same line as SELECT, but if these columns themselves require functions that take up more space, it is useful to put them on new lines. Likewise, ON is considered an elaboration of INNER JOIN. These lines of code are often indented to express the dependence on the previous line. If we include indentation in the code, the query is

SELECT

t.id,

t.column1,

t.column2,

t.column3,

r.column4

FROM table1 t

INNER JOIN table2 r

ON t.id = r.id

WHERE column1>100

ORDER BY column2 DESC;

I encourage you to develop good habits with how you write the SQL queries, both for other people to read your code, but more importantly, to make it easier for you yourself to read your code. You will be spending a lot of time developing and debugging SQL queries, and anything you do that cuts down the time to understand your own code will save you a lot of time and frustration in the long-run.

Quotes are only used in SQL code when referring to values of a character feature in one of the data tables. Single or double quotes are fine as long as they are not read as a termination of the Python variable that contains the SQL code.

For all of the queries we will write in the following examples, we will store the query as a string variable in Python. We will use the triple-quote syntax, which allows us to write a string that exists on multiple lines. So our SQL query definitions will look like this:

myquery = """

SELECT

t.id,

t.column1,

t.column2,

t.column3,

r.column4

FROM table1 t

INNER JOIN table2 r

ON t.id = r.id

WHERE column1>100

ORDER BY column2 DESC;

"""

We will then be able to pass the myquery variable to functions like pd.read_sql_query() to be evaluated.

Before we discuss specific examples of how to use SQL, we load the following packages:

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import sys

import os

import psycopg

from sqlalchemy import create_engine

import dotenv

7.4. SQL Joins#

There are many different kinds of joins, and the easiest way to see the difference between these types is to see what they do to real data.

7.4.1. Example Database: NFL and NBA Teams#

As an example, I create a PostgreSQL database that contains two tables: “nfl” contains the location and team name of all 32 NFL teams:

nfl_dict = {'city':['Buffalo','Miami','Boston','New York','Cleveland','Cincinnati',

'Pittsburgh','Baltimore','Kansas City','Las Vegas','Los Angeles','Denver',

'Nashville','Jacksonville','Houston','Indianapolis','Philadelphia','Dallas',

'Washington','Atlanta','Charlotte','Tampa Bay','New Orleans','San Francisco',

'Phoenix', 'Seattle','Chicago','Green Bay','Minneapolis','Detroit'],

'footballteam':['Buffalo Bills','Miami Dolphins','New England Patriots',

['New York Jets', 'New York Giants'],'Cleveland Browns','Cincinnati Bengals',

'Pittsburgh Steelers','Baltimore Ravens','Kansas City Chiefs',

'Las Vegas Raiders',['L.A. Chargers','L.A. Rams'],'Denver Broncos',

'Tennessee Titans','Jacksonville Jaguars','Houston Texans',

'Indianapolis Colts','Philadelphia Eagles','Dallas Cowboys',

'Washington Commanders','Atlanta Falcons','Carolina Panthers',

'Tampa Bay Buccaneers','New Orleans Saints', 'San Francisco 49ers',

'Arizona Cardinals','Seattle Seahawks','Chicago Bears',

'Green Bay Packers','Minnesota Vikings','Detroit Lions']}

nfl_df = pd.DataFrame(nfl_dict)

nfl_df

| city | footballteam | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Buffalo | Buffalo Bills |

| 1 | Miami | Miami Dolphins |

| 2 | Boston | New England Patriots |

| 3 | New York | [New York Jets, New York Giants] |

| 4 | Cleveland | Cleveland Browns |

| 5 | Cincinnati | Cincinnati Bengals |

| 6 | Pittsburgh | Pittsburgh Steelers |

| 7 | Baltimore | Baltimore Ravens |

| 8 | Kansas City | Kansas City Chiefs |

| 9 | Las Vegas | Las Vegas Raiders |

| 10 | Los Angeles | [L.A. Chargers, L.A. Rams] |

| 11 | Denver | Denver Broncos |

| 12 | Nashville | Tennessee Titans |

| 13 | Jacksonville | Jacksonville Jaguars |

| 14 | Houston | Houston Texans |

| 15 | Indianapolis | Indianapolis Colts |

| 16 | Philadelphia | Philadelphia Eagles |

| 17 | Dallas | Dallas Cowboys |

| 18 | Washington | Washington Commanders |

| 19 | Atlanta | Atlanta Falcons |

| 20 | Charlotte | Carolina Panthers |

| 21 | Tampa Bay | Tampa Bay Buccaneers |

| 22 | New Orleans | New Orleans Saints |

| 23 | San Francisco | San Francisco 49ers |

| 24 | Phoenix | Arizona Cardinals |

| 25 | Seattle | Seattle Seahawks |

| 26 | Chicago | Chicago Bears |

| 27 | Green Bay | Green Bay Packers |

| 28 | Minneapolis | Minnesota Vikings |

| 29 | Detroit | Detroit Lions |

This table is not in first normal form because the data are non-atomic (two teams from New York and two in Los Angeles), but this form is useful for illustrating what different SQL joins do. The second table contains the same information about NBA teams:

nba_dict = {'city':['Boston','New York','Philadelphia','Brooklyn','Toronto',

'Cleveland','Chicago','Detroit','Milwaukee','Indianapolis',

'Atlanta', 'Washington','Orlando','Miami','Charlotte',

'Los Angeles','San Francisco','Portland','Sacramento',

'Phoenix','San Antonio','Dallas','Houston','Oklahoma City',

'Minneapolis','Denver','Salt Lake City','Memphis','New Orleans'],

'basketballteam':['Boston Celtics','New York Knicks','Philadelphia 76ers',

'Brooklyn Nets','Toronto Raptors',

'Cleveland Cavaliers','Chicago Bulls','Detroit Pistons',

'Milwaukee Bucks','Indiana Pacers',

'Atlanta Hawks','Washington Wizards','Orlando Magic',

'Miami Heat','Charlotte Hornets',

['L.A. Lakers','L.A. Clippers'],'Golden State Warriors',

'Portland Trailblazers','Sacramento Kings',

'Phoenix Suns','San Antonio Spurs','Dallas Mavericks',

'Houston Rockets','Oklahoma City Thunder',

'Minnesota Timberwolves','Denver Nuggets',

'Utah Jazz','Memphis Grizzlies','New Orleans Pelicans']}

nba_df = pd.DataFrame(nba_dict)

nba_df

| city | basketballteam | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Boston | Boston Celtics |

| 1 | New York | New York Knicks |

| 2 | Philadelphia | Philadelphia 76ers |

| 3 | Brooklyn | Brooklyn Nets |

| 4 | Toronto | Toronto Raptors |

| 5 | Cleveland | Cleveland Cavaliers |

| 6 | Chicago | Chicago Bulls |

| 7 | Detroit | Detroit Pistons |

| 8 | Milwaukee | Milwaukee Bucks |

| 9 | Indianapolis | Indiana Pacers |

| 10 | Atlanta | Atlanta Hawks |

| 11 | Washington | Washington Wizards |

| 12 | Orlando | Orlando Magic |

| 13 | Miami | Miami Heat |

| 14 | Charlotte | Charlotte Hornets |

| 15 | Los Angeles | [L.A. Lakers, L.A. Clippers] |

| 16 | San Francisco | Golden State Warriors |

| 17 | Portland | Portland Trailblazers |

| 18 | Sacramento | Sacramento Kings |

| 19 | Phoenix | Phoenix Suns |

| 20 | San Antonio | San Antonio Spurs |

| 21 | Dallas | Dallas Mavericks |

| 22 | Houston | Houston Rockets |

| 23 | Oklahoma City | Oklahoma City Thunder |

| 24 | Minneapolis | Minnesota Timberwolves |

| 25 | Denver | Denver Nuggets |

| 26 | Salt Lake City | Utah Jazz |

| 27 | Memphis | Memphis Grizzlies |

| 28 | New Orleans | New Orleans Pelicans |

To create a PostgreSQL database with entities for the NFL and NBA teams, I first connect to the PostgreSQL server running on my local computer (see chapter 6 for a more detailed discussion of how this works). First I bring my PostgreSQL password into the local environment:

dotenv.load_dotenv()

pgpassword = os.getenv("POSTGRES_PASSWORD")

Then I access the server and establish a cursor for the server:

dbserver = psycopg.connect(

user='postgres',

password=pgpassword,

host='localhost'

)

dbserver.autocommit = True

cursor = dbserver.cursor()

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

OperationalError Traceback (most recent call last)

Cell In[5], line 1

----> 1 dbserver = psycopg.connect(

2 user='postgres',

3 password=pgpassword,

4 host='localhost'

5 )

6 dbserver.autocommit = True

7 cursor = dbserver.cursor()

File ~/.pyenv/versions/3.12.5/lib/python3.12/site-packages/psycopg/connection.py:119, in Connection.connect(cls, conninfo, autocommit, prepare_threshold, context, row_factory, cursor_factory, **kwargs)

117 if not rv:

118 assert last_ex

--> 119 raise last_ex.with_traceback(None)

121 rv._autocommit = bool(autocommit)

122 if row_factory:

OperationalError: connection failed: connection to server at "::1", port 5432 failed: could not receive data from server: Connection refused

I create an empty “teams” database:

try:

cursor.execute("CREATE DATABASE teams")

except:

cursor.execute("DROP DATABASE teams")

cursor.execute("CREATE DATABASE teams")

And I use the create_engine() function from sqalchemy to allow queries to the “teams” database:

engine = create_engine("postgresql+psycopg://{user}:{pw}@localhost/{db}"

.format(user="postgres", pw=pgpassword, db="teams"))

I add the nfl_df and nba_df dataframes to the “teams” database:

nfl_df.to_sql('nfl', con = engine, index=False, chunksize=1000, if_exists = 'replace')

nba_df.to_sql('nba', con = engine, index=False, chunksize=1000, if_exists = 'replace')

-1

I can now issue queries to the database. To read all of the data in the NFL table, for example, I type:

myquery = '''

SELECT *

FROM nfl

'''

pd.read_sql_query(myquery, con=engine)

| city | footballteam | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Buffalo | Buffalo Bills |

| 1 | Miami | Miami Dolphins |

| 2 | Boston | New England Patriots |

| 3 | New York | {"New York Jets","New York Giants"} |

| 4 | Cleveland | Cleveland Browns |

| 5 | Cincinnati | Cincinnati Bengals |

| 6 | Pittsburgh | Pittsburgh Steelers |

| 7 | Baltimore | Baltimore Ravens |

| 8 | Kansas City | Kansas City Chiefs |

| 9 | Las Vegas | Las Vegas Raiders |

| 10 | Los Angeles | {"L.A. Chargers","L.A. Rams"} |

| 11 | Denver | Denver Broncos |

| 12 | Nashville | Tennessee Titans |

| 13 | Jacksonville | Jacksonville Jaguars |

| 14 | Houston | Houston Texans |

| 15 | Indianapolis | Indianapolis Colts |

| 16 | Philadelphia | Philadelphia Eagles |

| 17 | Dallas | Dallas Cowboys |

| 18 | Washington | Washington Commanders |

| 19 | Atlanta | Atlanta Falcons |

| 20 | Charlotte | Carolina Panthers |

| 21 | Tampa Bay | Tampa Bay Buccaneers |

| 22 | New Orleans | New Orleans Saints |

| 23 | San Francisco | San Francisco 49ers |

| 24 | Phoenix | Arizona Cardinals |

| 25 | Seattle | Seattle Seahawks |

| 26 | Chicago | Chicago Bears |

| 27 | Green Bay | Green Bay Packers |

| 28 | Minneapolis | Minnesota Vikings |

| 29 | Detroit | Detroit Lions |

7.4.2. Types of Joins#

Joining data tables is the act of adding columns to an existing data table - that is, adding more features to existing records - by matching the rows in one table to the corresponding rows in another table. In a relational database, data tables can include a foreign key which serves as the primary key for another data table. Joins require matching a foreign key in one table to the corresponding primary key in another table. During the join, this foreign key and this primary key are both called indices. To perform a join with an SQL query, we specify the two tables in the database we want to join and the index in each table we will match on.

In the teams database, city is a primary key in both the “nfl” and “nba” tables, which also makes it a foreign key in both tables. Joining the “nfl” and “nba” tables by matching on city creates one data table in which the rows still represent cities and the columns list both the NBA and NFL teams in each city.

Not every city has both an NFL and an NBA team. Green Bay, for example, has a football team but no basketball team, and Sacramento has a basketball team but no football team. In a join, every row in a table either matches with one or more rows in the other table, or is unmatched. In this case, Cleveland in the NFL table is matched to a row in the NBA table because Cleveland has both a football and basketball team, but Oklahoma City in the NBA table is unmatched because there is no row for Oklahoma City in the NFL table.

The main difference between types of joins in SQL is their treatment of unmatched records. The following table summarizes the types of joins:

Type of join |

Definition |

|---|---|

Inner join |

Only keep the records that exist in both tables |

Left join |

Keep all the records in the first table listed (after |

Right join |

Keep all the records in the second table listed (after |

Full join |

Keep all of the records in both tables whether they are matched or not |

Anti join |

Keep only the records in the first table (after |

Natural join |

The same as any of the joins listed above, but no need to specify the indices as these are determined automatically by finding columns with the same name. If no columns share the same name, a natural join performs a cross join. If more than one pair of columns share names across the two data tables, natural joins assume that both are part of the index to match on. Use caution. |

Cross join |

Also called a Cartesian product. If the first dataframe has \(M\) rows and the second dataframe has \(N\) rows, the result has \(M\times N\) rows. Every row is a pairwise combination of values of each index. |

7.4.3. Inner Joins#

The syntax for an inner join is

SELECT *

FROM table1

INNER JOIN table2

ON table1.index_name = table2.index_name;

where table1 and table2 are the data tables we are joining, and table1.index_name and table2.index_name are the columns that contain the indices for tables 1 and 2. Alternatively, inner join is the default type of join, so that this syntax

SELECT *

FROM table1

JOIN table2

ON table1.index_name = table2.index_name;

also produces an inner join. I recommend typing INNER JOIN, however, to avoid confusing this type of join with other types.

In the case of the teams database, an inner join of the NFL and NBA tables yields a dataframe with one row for every city that has both a basketball and a football team. The SQL query that generates this data frame is:

myquery = """

SELECT *

FROM nfl

INNER JOIN nba

ON nfl.city = nba.city;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(myquery, con=engine)

| city | footballteam | city | basketballteam | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Miami | Miami Dolphins | Miami | Miami Heat |

| 1 | Boston | New England Patriots | Boston | Boston Celtics |

| 2 | New York | {"New York Jets","New York Giants"} | New York | New York Knicks |

| 3 | Cleveland | Cleveland Browns | Cleveland | Cleveland Cavaliers |

| 4 | Los Angeles | {"L.A. Chargers","L.A. Rams"} | Los Angeles | {"L.A. Lakers","L.A. Clippers"} |

| 5 | Denver | Denver Broncos | Denver | Denver Nuggets |

| 6 | Houston | Houston Texans | Houston | Houston Rockets |

| 7 | Indianapolis | Indianapolis Colts | Indianapolis | Indiana Pacers |

| 8 | Philadelphia | Philadelphia Eagles | Philadelphia | Philadelphia 76ers |

| 9 | Dallas | Dallas Cowboys | Dallas | Dallas Mavericks |

| 10 | Washington | Washington Commanders | Washington | Washington Wizards |

| 11 | Atlanta | Atlanta Falcons | Atlanta | Atlanta Hawks |

| 12 | Charlotte | Carolina Panthers | Charlotte | Charlotte Hornets |

| 13 | New Orleans | New Orleans Saints | New Orleans | New Orleans Pelicans |

| 14 | San Francisco | San Francisco 49ers | San Francisco | Golden State Warriors |

| 15 | Phoenix | Arizona Cardinals | Phoenix | Phoenix Suns |

| 16 | Chicago | Chicago Bears | Chicago | Chicago Bulls |

| 17 | Minneapolis | Minnesota Vikings | Minneapolis | Minnesota Timberwolves |

| 18 | Detroit | Detroit Lions | Detroit | Detroit Pistons |

Another way to write the inner join query is to use aliasing: specifying a smaller name or a single letter next to each data table in the query to simplify the syntax for ON. For example, I can alias the NFL data with f and the NBA data with b:

myquery = """

SELECT * FROM nfl f

INNER JOIN nba b

ON f.city = b.city;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(myquery, con=engine)

| city | footballteam | city | basketballteam | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Miami | Miami Dolphins | Miami | Miami Heat |

| 1 | Boston | New England Patriots | Boston | Boston Celtics |

| 2 | New York | {"New York Jets","New York Giants"} | New York | New York Knicks |

| 3 | Cleveland | Cleveland Browns | Cleveland | Cleveland Cavaliers |

| 4 | Los Angeles | {"L.A. Chargers","L.A. Rams"} | Los Angeles | {"L.A. Lakers","L.A. Clippers"} |

| 5 | Denver | Denver Broncos | Denver | Denver Nuggets |

| 6 | Houston | Houston Texans | Houston | Houston Rockets |

| 7 | Indianapolis | Indianapolis Colts | Indianapolis | Indiana Pacers |

| 8 | Philadelphia | Philadelphia Eagles | Philadelphia | Philadelphia 76ers |

| 9 | Dallas | Dallas Cowboys | Dallas | Dallas Mavericks |

| 10 | Washington | Washington Commanders | Washington | Washington Wizards |

| 11 | Atlanta | Atlanta Falcons | Atlanta | Atlanta Hawks |

| 12 | Charlotte | Carolina Panthers | Charlotte | Charlotte Hornets |

| 13 | New Orleans | New Orleans Saints | New Orleans | New Orleans Pelicans |

| 14 | San Francisco | San Francisco 49ers | San Francisco | Golden State Warriors |

| 15 | Phoenix | Arizona Cardinals | Phoenix | Phoenix Suns |

| 16 | Chicago | Chicago Bears | Chicago | Chicago Bulls |

| 17 | Minneapolis | Minnesota Vikings | Minneapolis | Minnesota Timberwolves |

| 18 | Detroit | Detroit Lions | Detroit | Detroit Pistons |

The two indices we match on do not necessarily have to have the same name. Supposing that the “city” column in each data table was named “location” in the NFL table and “town” in the NBA table, the syntax for the inner join would have been:

SELECT *

FROM nfl f

INNER JOIN nba b

ON f.location = b.town;

7.4.4. Left and Right Joins#

The syntax for a left join is

SELECT *

FROM table1

LEFT JOIN table2

ON table1.index_name = table2.index_name;

and the syntax for a right join is

SELECT *

FROM table1

RIGHT JOIN table2

ON table1.index_name = table2.index_name;

In the case of the teams database, if we list the NFL table next to FROM and the NBA data with the JOIN statement, then left join lists all of the cities with an NFL team, and also displays the NBA team in that city if one exists. Otherwise, the syntax places None in the cell where the NBA team would be. For the teams database, the syntax for a left join is:

myquery = """

SELECT *

FROM nfl f

LEFT JOIN nba b

ON f.city = b.city;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(myquery, con=engine)

| city | footballteam | city | basketballteam | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Buffalo | Buffalo Bills | None | None |

| 1 | Miami | Miami Dolphins | Miami | Miami Heat |

| 2 | Boston | New England Patriots | Boston | Boston Celtics |

| 3 | New York | {"New York Jets","New York Giants"} | New York | New York Knicks |

| 4 | Cleveland | Cleveland Browns | Cleveland | Cleveland Cavaliers |

| 5 | Cincinnati | Cincinnati Bengals | None | None |

| 6 | Pittsburgh | Pittsburgh Steelers | None | None |

| 7 | Baltimore | Baltimore Ravens | None | None |

| 8 | Kansas City | Kansas City Chiefs | None | None |

| 9 | Las Vegas | Las Vegas Raiders | None | None |

| 10 | Los Angeles | {"L.A. Chargers","L.A. Rams"} | Los Angeles | {"L.A. Lakers","L.A. Clippers"} |

| 11 | Denver | Denver Broncos | Denver | Denver Nuggets |

| 12 | Nashville | Tennessee Titans | None | None |

| 13 | Jacksonville | Jacksonville Jaguars | None | None |

| 14 | Houston | Houston Texans | Houston | Houston Rockets |

| 15 | Indianapolis | Indianapolis Colts | Indianapolis | Indiana Pacers |

| 16 | Philadelphia | Philadelphia Eagles | Philadelphia | Philadelphia 76ers |

| 17 | Dallas | Dallas Cowboys | Dallas | Dallas Mavericks |

| 18 | Washington | Washington Commanders | Washington | Washington Wizards |

| 19 | Atlanta | Atlanta Falcons | Atlanta | Atlanta Hawks |

| 20 | Charlotte | Carolina Panthers | Charlotte | Charlotte Hornets |

| 21 | Tampa Bay | Tampa Bay Buccaneers | None | None |

| 22 | New Orleans | New Orleans Saints | New Orleans | New Orleans Pelicans |

| 23 | San Francisco | San Francisco 49ers | San Francisco | Golden State Warriors |

| 24 | Phoenix | Arizona Cardinals | Phoenix | Phoenix Suns |

| 25 | Seattle | Seattle Seahawks | None | None |

| 26 | Chicago | Chicago Bears | Chicago | Chicago Bulls |

| 27 | Green Bay | Green Bay Packers | None | None |

| 28 | Minneapolis | Minnesota Vikings | Minneapolis | Minnesota Timberwolves |

| 29 | Detroit | Detroit Lions | Detroit | Detroit Pistons |

Likewise, the right join displays all the cities with an NBA team, along with the NFL team in that city, if one exists:

myquery = """

SELECT *

FROM nfl f

RIGHT JOIN nba b

ON f.city = b.city;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(myquery, con=engine)

| city | footballteam | city | basketballteam | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Boston | New England Patriots | Boston | Boston Celtics |

| 1 | New York | {"New York Jets","New York Giants"} | New York | New York Knicks |

| 2 | Philadelphia | Philadelphia Eagles | Philadelphia | Philadelphia 76ers |

| 3 | None | None | Brooklyn | Brooklyn Nets |

| 4 | None | None | Toronto | Toronto Raptors |

| 5 | Cleveland | Cleveland Browns | Cleveland | Cleveland Cavaliers |

| 6 | Chicago | Chicago Bears | Chicago | Chicago Bulls |

| 7 | Detroit | Detroit Lions | Detroit | Detroit Pistons |

| 8 | None | None | Milwaukee | Milwaukee Bucks |

| 9 | Indianapolis | Indianapolis Colts | Indianapolis | Indiana Pacers |

| 10 | Atlanta | Atlanta Falcons | Atlanta | Atlanta Hawks |

| 11 | Washington | Washington Commanders | Washington | Washington Wizards |

| 12 | None | None | Orlando | Orlando Magic |

| 13 | Miami | Miami Dolphins | Miami | Miami Heat |

| 14 | Charlotte | Carolina Panthers | Charlotte | Charlotte Hornets |

| 15 | Los Angeles | {"L.A. Chargers","L.A. Rams"} | Los Angeles | {"L.A. Lakers","L.A. Clippers"} |

| 16 | San Francisco | San Francisco 49ers | San Francisco | Golden State Warriors |

| 17 | None | None | Portland | Portland Trailblazers |

| 18 | None | None | Sacramento | Sacramento Kings |

| 19 | Phoenix | Arizona Cardinals | Phoenix | Phoenix Suns |

| 20 | None | None | San Antonio | San Antonio Spurs |

| 21 | Dallas | Dallas Cowboys | Dallas | Dallas Mavericks |

| 22 | Houston | Houston Texans | Houston | Houston Rockets |

| 23 | None | None | Oklahoma City | Oklahoma City Thunder |

| 24 | Minneapolis | Minnesota Vikings | Minneapolis | Minnesota Timberwolves |

| 25 | Denver | Denver Broncos | Denver | Denver Nuggets |

| 26 | None | None | Salt Lake City | Utah Jazz |

| 27 | None | None | Memphis | Memphis Grizzlies |

| 28 | New Orleans | New Orleans Saints | New Orleans | New Orleans Pelicans |

For the left and right joins, changing which data table appears along with FROM and which data table appears along with JOIN accomplishes the same thing as changing a left join to a right join.

7.4.5. Full (Outer) Join#

A full join, also called an outer join, keeps all of the records that exist in both tables, whether or not they are matched. Full joins will return a data frame with at least as many rows as the larger of the two data tables in the join because it contains all records that appear in either data frame. Most tutorials on SQL offer a warning about full joins that these queries can result in massive amounts of data being returned, and full joins are not implemented for MySQL databases. For systems like PostgreSQL in which full joins are allowed, the syntax for a full join is

SELECT *

FROM table1

FULL JOIN table2

ON table1.index_name = table2.index_name;

For the teams database, a full join produces a data frame with one row for every city with an NFL team or an NBA team or both:

myquery = """

SELECT *

FROM nfl f

FULL JOIN nba b

ON f.city = b.city;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(myquery, con=engine)

| city | footballteam | city | basketballteam | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Buffalo | Buffalo Bills | None | None |

| 1 | Miami | Miami Dolphins | Miami | Miami Heat |

| 2 | Boston | New England Patriots | Boston | Boston Celtics |

| 3 | New York | {"New York Jets","New York Giants"} | New York | New York Knicks |

| 4 | Cleveland | Cleveland Browns | Cleveland | Cleveland Cavaliers |

| 5 | Cincinnati | Cincinnati Bengals | None | None |

| 6 | Pittsburgh | Pittsburgh Steelers | None | None |

| 7 | Baltimore | Baltimore Ravens | None | None |

| 8 | Kansas City | Kansas City Chiefs | None | None |

| 9 | Las Vegas | Las Vegas Raiders | None | None |

| 10 | Los Angeles | {"L.A. Chargers","L.A. Rams"} | Los Angeles | {"L.A. Lakers","L.A. Clippers"} |

| 11 | Denver | Denver Broncos | Denver | Denver Nuggets |

| 12 | Nashville | Tennessee Titans | None | None |

| 13 | Jacksonville | Jacksonville Jaguars | None | None |

| 14 | Houston | Houston Texans | Houston | Houston Rockets |

| 15 | Indianapolis | Indianapolis Colts | Indianapolis | Indiana Pacers |

| 16 | Philadelphia | Philadelphia Eagles | Philadelphia | Philadelphia 76ers |

| 17 | Dallas | Dallas Cowboys | Dallas | Dallas Mavericks |

| 18 | Washington | Washington Commanders | Washington | Washington Wizards |

| 19 | Atlanta | Atlanta Falcons | Atlanta | Atlanta Hawks |

| 20 | Charlotte | Carolina Panthers | Charlotte | Charlotte Hornets |

| 21 | Tampa Bay | Tampa Bay Buccaneers | None | None |

| 22 | New Orleans | New Orleans Saints | New Orleans | New Orleans Pelicans |

| 23 | San Francisco | San Francisco 49ers | San Francisco | Golden State Warriors |

| 24 | Phoenix | Arizona Cardinals | Phoenix | Phoenix Suns |

| 25 | Seattle | Seattle Seahawks | None | None |

| 26 | Chicago | Chicago Bears | Chicago | Chicago Bulls |

| 27 | Green Bay | Green Bay Packers | None | None |

| 28 | Minneapolis | Minnesota Vikings | Minneapolis | Minnesota Timberwolves |

| 29 | Detroit | Detroit Lions | Detroit | Detroit Pistons |

| 30 | None | None | Milwaukee | Milwaukee Bucks |

| 31 | None | None | Oklahoma City | Oklahoma City Thunder |

| 32 | None | None | Portland | Portland Trailblazers |

| 33 | None | None | Brooklyn | Brooklyn Nets |

| 34 | None | None | Sacramento | Sacramento Kings |

| 35 | None | None | Memphis | Memphis Grizzlies |

| 36 | None | None | San Antonio | San Antonio Spurs |

| 37 | None | None | Salt Lake City | Utah Jazz |

| 38 | None | None | Orlando | Orlando Magic |

| 39 | None | None | Toronto | Toronto Raptors |

Although there are 30 cities with at least one NFL team and 29 cities with at least one NBA team, there are 40 cities with at least one team from one of these two leagues.

7.4.6. Anti-Joins#

An anti-join leaves us with all of the records in the first data table that do not appear in the second table. There is no “ANTI JOIN” syntax in SQL, but the behavior of an anti-join can be generated by including the WHERE clause along with LEFT JOIN. The syntax for an anti-join is

SELECT * FROM table1

LEFT JOIN table2

ON table1.index_name = table2.index_name

WHERE table2.index_name is NULL;

The WHERE statement is used to draw a selection of rows from a data table that make a specified logical condition true. After performing a left join we have a data table with all of the rows in the first table along with the data for those rows in the second table if the row had a match in the second table. Typing WHERE table2.index_name is NULL restricts this data table to only the rows that do not have a value of the index in the second table, meaning there was no match. For the teams database, the anti-join of the NFL and NBA tables yields a dataframe of all the cities with an NFL team but no NBA team:

myquery = """

SELECT * FROM nfl f

LEFT JOIN nba b

ON f.city = b.city

WHERE b.city is NULL;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(myquery, con=engine)

| city | footballteam | city | basketballteam | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Buffalo | Buffalo Bills | None | None |

| 1 | Cincinnati | Cincinnati Bengals | None | None |

| 2 | Pittsburgh | Pittsburgh Steelers | None | None |

| 3 | Baltimore | Baltimore Ravens | None | None |

| 4 | Kansas City | Kansas City Chiefs | None | None |

| 5 | Las Vegas | Las Vegas Raiders | None | None |

| 6 | Nashville | Tennessee Titans | None | None |

| 7 | Jacksonville | Jacksonville Jaguars | None | None |

| 8 | Tampa Bay | Tampa Bay Buccaneers | None | None |

| 9 | Seattle | Seattle Seahawks | None | None |

| 10 | Green Bay | Green Bay Packers | None | None |

7.4.7. Natural Joins#

One annoying thing about all of the joins shown above is that we end up with two columns that contain the same information. In the case of the team database, we have two city columns that are always either equal, or else one is missing. But when one of the city columns says “None”, the team from that table also says “None”, so the missingness in the city column does not provide additional information.

It might make sense to use a different kind of join that understands that the two city columns contain the same information and includes only one of these columns. A natural join does two things differently from the other joins described here:

A natural join removes duplicated columns from the output data.

A natural join detects the indices automatically by assuming columns that share the same name are part indices.

If done correctly, a natural join saves some work constructing the query as the indices are detected automatically, and provides cleaner output. Any of the joins described above can be done as a natural join by adding NATURAL in front of INNER, LEFT, RIGHT, or FULL. If there are no columns that share the same name, a natural join instead performs a cross join (described below).

The following query performs a natural inner join:

myquery = """

SELECT * from nfl

NATURAL INNER JOIN nba

"""

pd.read_sql_query(myquery, con=engine)

| city | footballteam | basketballteam | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Miami | Miami Dolphins | Miami Heat |

| 1 | Boston | New England Patriots | Boston Celtics |

| 2 | New York | {"New York Jets","New York Giants"} | New York Knicks |

| 3 | Cleveland | Cleveland Browns | Cleveland Cavaliers |

| 4 | Los Angeles | {"L.A. Chargers","L.A. Rams"} | {"L.A. Lakers","L.A. Clippers"} |

| 5 | Denver | Denver Broncos | Denver Nuggets |

| 6 | Houston | Houston Texans | Houston Rockets |

| 7 | Indianapolis | Indianapolis Colts | Indiana Pacers |

| 8 | Philadelphia | Philadelphia Eagles | Philadelphia 76ers |

| 9 | Dallas | Dallas Cowboys | Dallas Mavericks |

| 10 | Washington | Washington Commanders | Washington Wizards |

| 11 | Atlanta | Atlanta Falcons | Atlanta Hawks |

| 12 | Charlotte | Carolina Panthers | Charlotte Hornets |

| 13 | New Orleans | New Orleans Saints | New Orleans Pelicans |

| 14 | San Francisco | San Francisco 49ers | Golden State Warriors |

| 15 | Phoenix | Arizona Cardinals | Phoenix Suns |

| 16 | Chicago | Chicago Bears | Chicago Bulls |

| 17 | Minneapolis | Minnesota Vikings | Minnesota Timberwolves |

| 18 | Detroit | Detroit Lions | Detroit Pistons |

Natural joins are controversial, however, and many data scientists choose not to use them at all. The danger is that if two columns unexpectedly have the same name (it can be hard to keep track of all of the features’ names in big databases) then a natural join will match on the wrong indices. This Stack Overflow post gets into this debate, and one response made a forceful argument against natural joins:

Collapsing columns in the output is the least-important aspect of a natural join. The things you need to know are (A) it automatically joins on fields of the same name and (B) it will f— up your s— when you least expect it. In my world, using a natural join is grounds for dismissal… . Say you have a natural join between

CustomersandEmployees, joining onEmployeeID. Employees also has aManagerIDfield. Everything’s fine. Then, some day, someone adds aManagerIDfield to theCustomerstable. Your join will not break (that would be a mercy), instead it will now include a second field, and work incorrectly. Thus, a seemingly harmless change can break something only distantly related. VERY BAD. The only upside of a natural join is saving a little typing, and the downside is substantial.

To demonstrate how a natural join can go wrong, suppose that in both the NFL and NBA tables the columns were named city and team. The following code creates versions of these tables with footballteam and basketballteam each renamed to team and stores these tables in the database as “nfl2” and “nba2”:

nfl2 = pd.read_sql_query("SELECT city, footballteam as team FROM nfl;", con=engine)

nba2 = pd.read_sql_query("SELECT city, basketballteam as team FROM nba;", con=engine)

nfl2.to_sql('nfl2', con = engine, index=False, chunksize=1000, if_exists = 'replace')

nba2.to_sql('nba2', con = engine, index=False, chunksize=1000, if_exists = 'replace')

-1

Now a natural inner join between “nfl2” and “nba2” yields a dataframe with no records:

myquery = """

SELECT * FROM nfl2

NATURAL INNER JOIN nba2;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(myquery, con=engine)

| city | team |

|---|

The reason why there are no records is that the natural join automatically chooses both city and team to be part of the index, and records are only kept in the inner join if they match on both city and team. There are many matches for city, but no matches for both city and team.

In contrast, a regular inner join still works fine:

myquery = """

SELECT * FROM nfl2 f

INNER JOIN nba2 b

ON f.city = b.city;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(myquery, con=engine)

| city | team | city | team | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Miami | Miami Dolphins | Miami | Miami Heat |

| 1 | Boston | New England Patriots | Boston | Boston Celtics |

| 2 | New York | {"New York Jets","New York Giants"} | New York | New York Knicks |

| 3 | Cleveland | Cleveland Browns | Cleveland | Cleveland Cavaliers |

| 4 | Los Angeles | {"L.A. Chargers","L.A. Rams"} | Los Angeles | {"L.A. Lakers","L.A. Clippers"} |

| 5 | Denver | Denver Broncos | Denver | Denver Nuggets |

| 6 | Houston | Houston Texans | Houston | Houston Rockets |

| 7 | Indianapolis | Indianapolis Colts | Indianapolis | Indiana Pacers |

| 8 | Philadelphia | Philadelphia Eagles | Philadelphia | Philadelphia 76ers |

| 9 | Dallas | Dallas Cowboys | Dallas | Dallas Mavericks |

| 10 | Washington | Washington Commanders | Washington | Washington Wizards |

| 11 | Atlanta | Atlanta Falcons | Atlanta | Atlanta Hawks |

| 12 | Charlotte | Carolina Panthers | Charlotte | Charlotte Hornets |

| 13 | New Orleans | New Orleans Saints | New Orleans | New Orleans Pelicans |

| 14 | San Francisco | San Francisco 49ers | San Francisco | Golden State Warriors |

| 15 | Phoenix | Arizona Cardinals | Phoenix | Phoenix Suns |

| 16 | Chicago | Chicago Bears | Chicago | Chicago Bulls |

| 17 | Minneapolis | Minnesota Vikings | Minneapolis | Minnesota Timberwolves |

| 18 | Detroit | Detroit Lions | Detroit | Detroit Pistons |

To safely use natural joins, first make certain that the indices you intend to match on have the same name, and then make sure that no other columns in the two data tables share a name.

7.4.8. Cross Joins#

A round robin is a method of organizing a competitive tournament. In a round robin, every team or participant plays every other team or participant once. A cross join, also called a Cartesian product, is a round robin for matching values of the index in one data table to values of the index in the other data table. Every value of the index in the first data table is matched once to every distinct value of the index in the second data table. Cross joins are memory-intensive: if the first data table has \(M\) rows and the second data table has \(N\) rows, the cross join output is a data table with \(M\times N\) rows. In general cross joins are not good ways to combine data entities, and they fail to match strictly like units. But cross joins are useful for constructing data that contain all possible pairings, if that’s what a situation calls for.

The syntax for generating a cross join is

SELECT * FROM table1

CROSS JOIN table2;

There is no ON statement in this query because it is not needed to match each row in table1 to every row in table2. For the teams database, the cross join generates the following output:

myquery = """

SELECT * FROM nfl

CROSS JOIN nba;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(myquery, con=engine)

| city | footballteam | city | basketballteam | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Buffalo | Buffalo Bills | Boston | Boston Celtics |

| 1 | Buffalo | Buffalo Bills | New York | New York Knicks |

| 2 | Buffalo | Buffalo Bills | Philadelphia | Philadelphia 76ers |

| 3 | Buffalo | Buffalo Bills | Brooklyn | Brooklyn Nets |

| 4 | Buffalo | Buffalo Bills | Toronto | Toronto Raptors |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 865 | Detroit | Detroit Lions | Minneapolis | Minnesota Timberwolves |

| 866 | Detroit | Detroit Lions | Denver | Denver Nuggets |

| 867 | Detroit | Detroit Lions | Salt Lake City | Utah Jazz |

| 868 | Detroit | Detroit Lions | Memphis | Memphis Grizzlies |

| 869 | Detroit | Detroit Lions | New Orleans | New Orleans Pelicans |

870 rows × 4 columns

7.4.9. Multiple Joins in One Query#

All of the examples above show a single join between two data tables, but many situations will require you to join multiple tables. it is possible to join many tables in one SQL query. The syntax to perform an inner join between two tables, then an inner join between the result and a third table is

SELECT * FROM table1

INNER JOIN table2

ON table1.index_name = table2.index_name

INNER JOIN table 3

ON table1.index_name = table3.index_name;

To demonstrate how multiple joins can work, I add a third table to the teams database that contains all of the Major League Baseball teams:

mlb_dict = {'city': ['New York', 'Boston', 'Toronto', 'Baltimore', 'Tampa Bay',

'Cleveland', 'Chicago', 'Kansas City', 'Minneapolis', 'Detroit',

'Houston', 'Anaheim', 'Dallas', 'Seattle', 'Oakland',

'Philadelphia', 'Miami', 'Washington', 'Atlanta', 'Cincinnati',

'Milwaukee', 'St. Louis', 'Pittsburgh', 'Los Angeles', 'San Francisco',

'San Diego', 'Denver', 'Phoenix'],

'baseballteam': [['New York Mets', 'New York Yankees'], 'Boston Red Sox', 'Toronto Blue Jays',

'Baltimore Orioles', 'Tampa Bay Rays', 'Cleveland Guardians',

['Chicago White Sox', 'Chicago Cubs'], 'Kansas City Royals', 'Minnesota Twins',

'Detriot Tigers', 'Houston Astros', 'Anaheim Angels', 'Texas Rangers',

'Seattle Mariners', 'Oakland Athletics', 'Philadelphia Phillies',

'Miami Marlins', 'Washington Nationals', 'Atlanta Braves', 'Cincinnati Reds',

'Milwaukee Brewers', 'St. Louis Cardinals', 'Pittsburgh Pirates', 'Los Angeles Dodgers',

'San Francisco Giants', 'San Diego Padres', 'Colorado Rockies', 'Arizona Diamondbacks']}

mlb_df = pd.DataFrame(mlb_dict)

mlb_df.to_sql('mlb', con = engine, index=False, chunksize=1000, if_exists = 'replace')

-1

We can first inner join the NFL and NBA data tables to keep only the cities with both an NFL and an NBA team, then we can inner join the result with the MLB data to keep only the cities with teams in all three sports:

myquery = """

SELECT * FROM nfl f

INNER JOIN nba b

ON f.city = b.city

INNER JOIN mlb m

ON f.city = m.city;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(myquery, con=engine)

| city | footballteam | city | basketballteam | city | baseballteam | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Atlanta | Atlanta Falcons | Atlanta | Atlanta Hawks | Atlanta | Atlanta Braves |

| 1 | Boston | New England Patriots | Boston | Boston Celtics | Boston | Boston Red Sox |

| 2 | Chicago | Chicago Bears | Chicago | Chicago Bulls | Chicago | {"Chicago White Sox","Chicago Cubs"} |

| 3 | Cleveland | Cleveland Browns | Cleveland | Cleveland Cavaliers | Cleveland | Cleveland Guardians |

| 4 | Dallas | Dallas Cowboys | Dallas | Dallas Mavericks | Dallas | Texas Rangers |

| 5 | Denver | Denver Broncos | Denver | Denver Nuggets | Denver | Colorado Rockies |

| 6 | Detroit | Detroit Lions | Detroit | Detroit Pistons | Detroit | Detriot Tigers |

| 7 | Houston | Houston Texans | Houston | Houston Rockets | Houston | Houston Astros |

| 8 | Los Angeles | {"L.A. Chargers","L.A. Rams"} | Los Angeles | {"L.A. Lakers","L.A. Clippers"} | Los Angeles | Los Angeles Dodgers |

| 9 | Miami | Miami Dolphins | Miami | Miami Heat | Miami | Miami Marlins |

| 10 | Minneapolis | Minnesota Vikings | Minneapolis | Minnesota Timberwolves | Minneapolis | Minnesota Twins |

| 11 | New York | {"New York Jets","New York Giants"} | New York | New York Knicks | New York | {"New York Mets","New York Yankees"} |

| 12 | Philadelphia | Philadelphia Eagles | Philadelphia | Philadelphia 76ers | Philadelphia | Philadelphia Phillies |

| 13 | Phoenix | Arizona Cardinals | Phoenix | Phoenix Suns | Phoenix | Arizona Diamondbacks |

| 14 | San Francisco | San Francisco 49ers | San Francisco | Golden State Warriors | San Francisco | San Francisco Giants |

| 15 | Washington | Washington Commanders | Washington | Washington Wizards | Washington | Washington Nationals |

Things get more complicated when we consider left, right, and full joins in a multiple table context. The trick is to think about the set of records that is required, to express that set in set theoretical notation, and to find the right combination of joins that matches that set theoretical statement.

For example, to obtain all cities with both an NFL and NBA team, also listing the MLB team if one exists in that city, we first inner join the NFL table to the NBA table, then we left join either the NFL’s or NBA’s city index to the MLB’s city column:

myquery = """

SELECT * FROM nfl f

INNER JOIN nba b

ON f.city = b.city

LEFT JOIN mlb m

ON f.city = m.city;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(myquery, con=engine)

| city | footballteam | city | basketballteam | city | baseballteam | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Atlanta | Atlanta Falcons | Atlanta | Atlanta Hawks | Atlanta | Atlanta Braves |

| 1 | Boston | New England Patriots | Boston | Boston Celtics | Boston | Boston Red Sox |

| 2 | Charlotte | Carolina Panthers | Charlotte | Charlotte Hornets | None | None |

| 3 | Chicago | Chicago Bears | Chicago | Chicago Bulls | Chicago | {"Chicago White Sox","Chicago Cubs"} |

| 4 | Cleveland | Cleveland Browns | Cleveland | Cleveland Cavaliers | Cleveland | Cleveland Guardians |

| 5 | Dallas | Dallas Cowboys | Dallas | Dallas Mavericks | Dallas | Texas Rangers |

| 6 | Denver | Denver Broncos | Denver | Denver Nuggets | Denver | Colorado Rockies |

| 7 | Detroit | Detroit Lions | Detroit | Detroit Pistons | Detroit | Detriot Tigers |

| 8 | Houston | Houston Texans | Houston | Houston Rockets | Houston | Houston Astros |

| 9 | Indianapolis | Indianapolis Colts | Indianapolis | Indiana Pacers | None | None |

| 10 | Los Angeles | {"L.A. Chargers","L.A. Rams"} | Los Angeles | {"L.A. Lakers","L.A. Clippers"} | Los Angeles | Los Angeles Dodgers |

| 11 | Miami | Miami Dolphins | Miami | Miami Heat | Miami | Miami Marlins |

| 12 | Minneapolis | Minnesota Vikings | Minneapolis | Minnesota Timberwolves | Minneapolis | Minnesota Twins |

| 13 | New Orleans | New Orleans Saints | New Orleans | New Orleans Pelicans | None | None |

| 14 | New York | {"New York Jets","New York Giants"} | New York | New York Knicks | New York | {"New York Mets","New York Yankees"} |

| 15 | Philadelphia | Philadelphia Eagles | Philadelphia | Philadelphia 76ers | Philadelphia | Philadelphia Phillies |

| 16 | Phoenix | Arizona Cardinals | Phoenix | Phoenix Suns | Phoenix | Arizona Diamondbacks |

| 17 | San Francisco | San Francisco 49ers | San Francisco | Golden State Warriors | San Francisco | San Francisco Giants |

| 18 | Washington | Washington Commanders | Washington | Washington Wizards | Washington | Washington Nationals |

To narrow the records to teams with a baseball team and a basketball team, but no football team, first we inner join the MLB and NBA data tables, then perform an anti-join with the NFL data:

myquery = """

SELECT * FROM mlb m

INNER JOIN nba b

ON m.city=b.city

LEFT JOIN nfl f

ON m.city = f.city

WHERE f.city is NULL;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(myquery, con=engine)

| city | baseballteam | city | basketballteam | city | footballteam | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Toronto | Toronto Blue Jays | Toronto | Toronto Raptors | None | None |

| 1 | Milwaukee | Milwaukee Brewers | Milwaukee | Milwaukee Bucks | None | None |

7.4.10. Joins on More Than One Index#

Sometimes more than one column comprises the primary key for a table. The general syntax for joining two tables on more than one index adds the AND clause to the standard SQL join syntax:

SELECT * FROM table1

INNER JOIN table2

ON table1.index1 = table2.index2

AND table1.anotherindex1 = table2.anotherindex2;

Suppose for example that the NBA table and MLB table also contained records for minor league teams in the NBA G-League or the MLB AAA system. Some cities have both major and minor league teams in the same sport. Washington, for example, has an NBA team, the Wizards, and a minor league basketball team, the Capital City Go-Gos. Suppose that both the NBA and MLB tables have a column leaguetype that marks each team as “major” or “minor”, and that we want to match on both city and league type. The syntax to do so is

SELECT * FROM nba b

INNER JOIN mlb m

ON b.city = m.city

AND b.leaguetype = m.leaguetype;

7.5. SQL Create, Update, and Delete Operations#

Once a database exists and is populated with data, most changes to the data will be small and incremental. We might add a few records, edit a couple, or delete one or two. There are straightforward SQL commands for creating, updating, and deleting records. To issue these queries, however, we cannot use the pd.read_sql_query() function as this function is only for read operations. Instead, we can use the .execute() method as applied to either the cursor for the database we are working with, or the sqlalchemy engine. Specific examples are shown below.

7.5.1. Creating New Records#

An existing database has a schema, an overarching organizational blueprint for the database, that describes the different tables in the database, and within each table what the columns are and what kinds of data can be input into the columns. Creating new data generally works within an established schema. That means we enter new datapoints into existing columns, matching the data type that must exist in those columns.

The SQL syntax to create new data is

INSERT INTO table (column1, column2, ...)

VALUES (value1, value2, ...);

This syntax requires us to specify the key elements of the schema that identify a location in the database: the table and the columns. The values need to be listed in the same order as the columns, and character values need to be enclosed in single quotes.

To add a new observation to the NBA table (bring back the Sonics!) we can type:

myquery = """

INSERT INTO nba (city, basketballteam)

VALUES ('Seattle', 'Seattle Supersonics');

"""

One tricky thing about the latest version of sqlalchemy is that create, update, and delete operations must be executed in the following way:

from sqlalchemy import text

with engine.connect() as conn:

result = conn.execute(text(myquery))

conn.commit()

Here the engine variable is the sqlalchemy engine we previously established for the teams database. We establish a connection to this database with the .connect() method, then apply the .execute() method to the connection, using sqlalchemy’s text parser for the SQL code. Finally we use .commit() on the changes to save them for future read operations. Now, when we look at the data, we see the Seattle Supersonics included along with all the other NBA teams:

pd.read_sql_query("SELECT * FROM nba", con=engine)

| city | basketballteam | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Boston | Boston Celtics |

| 1 | New York | New York Knicks |

| 2 | Philadelphia | Philadelphia 76ers |

| 3 | Brooklyn | Brooklyn Nets |

| 4 | Toronto | Toronto Raptors |

| 5 | Cleveland | Cleveland Cavaliers |

| 6 | Chicago | Chicago Bulls |

| 7 | Detroit | Detroit Pistons |

| 8 | Milwaukee | Milwaukee Bucks |

| 9 | Indianapolis | Indiana Pacers |

| 10 | Atlanta | Atlanta Hawks |

| 11 | Washington | Washington Wizards |

| 12 | Orlando | Orlando Magic |

| 13 | Miami | Miami Heat |

| 14 | Charlotte | Charlotte Hornets |

| 15 | Los Angeles | {"L.A. Lakers","L.A. Clippers"} |

| 16 | San Francisco | Golden State Warriors |

| 17 | Portland | Portland Trailblazers |

| 18 | Sacramento | Sacramento Kings |

| 19 | Phoenix | Phoenix Suns |

| 20 | San Antonio | San Antonio Spurs |

| 21 | Dallas | Dallas Mavericks |

| 22 | Houston | Houston Rockets |

| 23 | Oklahoma City | Oklahoma City Thunder |

| 24 | Minneapolis | Minnesota Timberwolves |

| 25 | Denver | Denver Nuggets |

| 26 | Salt Lake City | Utah Jazz |

| 27 | Memphis | Memphis Grizzlies |

| 28 | New Orleans | New Orleans Pelicans |

| 29 | Seattle | Seattle Supersonics |

7.5.2. Editing Existing Records#

Instead of creating a new record, there are situations in which we want to edit an existing record. To revise a record, we use the following SQL syntax:

UPDATE table

SET column2 = newvalue

WHERE logicalcondition;

In this case, SET specifies the change we want to make to a particular column. But we don’t want to change all of the values of the column, so we use WHERE to specify a logical condition to identify the rows we want to change. A logical condition is a statement that is true on some rows and false on others, and the data update happens only on the rows for which the condition is true.

Suppose we want to change the name of the Charlotte Hornets back to the Charlotte Bobcats (sorry, Charlotte). We can use the following code:

myquery = """

UPDATE nba

SET basketballteam = 'Charlotte Bobcats'

WHERE city = 'Charlotte';

"""

with engine.connect() as conn:

result = conn.execute(text(myquery))

conn.commit()

Here the query says to update values in the NBA table by changing basketballteam to Charlotte Bobcats, but only when city is Charlotte. This update now appears in the NBA data:

pd.read_sql_query("SELECT * FROM nba", con=engine)

| city | basketballteam | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Boston | Boston Celtics |

| 1 | New York | New York Knicks |

| 2 | Philadelphia | Philadelphia 76ers |

| 3 | Brooklyn | Brooklyn Nets |

| 4 | Toronto | Toronto Raptors |

| 5 | Cleveland | Cleveland Cavaliers |

| 6 | Chicago | Chicago Bulls |

| 7 | Detroit | Detroit Pistons |

| 8 | Milwaukee | Milwaukee Bucks |

| 9 | Indianapolis | Indiana Pacers |

| 10 | Atlanta | Atlanta Hawks |

| 11 | Washington | Washington Wizards |

| 12 | Orlando | Orlando Magic |

| 13 | Miami | Miami Heat |

| 14 | Los Angeles | {"L.A. Lakers","L.A. Clippers"} |

| 15 | San Francisco | Golden State Warriors |

| 16 | Portland | Portland Trailblazers |

| 17 | Sacramento | Sacramento Kings |

| 18 | Phoenix | Phoenix Suns |

| 19 | San Antonio | San Antonio Spurs |

| 20 | Dallas | Dallas Mavericks |

| 21 | Houston | Houston Rockets |

| 22 | Oklahoma City | Oklahoma City Thunder |

| 23 | Minneapolis | Minnesota Timberwolves |

| 24 | Denver | Denver Nuggets |

| 25 | Salt Lake City | Utah Jazz |

| 26 | Memphis | Memphis Grizzlies |

| 27 | New Orleans | New Orleans Pelicans |

| 28 | Seattle | Seattle Supersonics |

| 29 | Charlotte | Charlotte Bobcats |

7.5.3. Deleting Records#

Sometimes you might need to delete records from a database. These situations should be rare. If a record is no longer relevant for a particular use, it is always better to leave the record in the database and use another column to denote new information that can be used to filter records later. If there are mistakes in data entry, it’s better to edit existing records than to delete those records outright. If you must delete a record, the syntax to do so is

DELETE

FROM table

WHERE logicalcondition;

First specify the table, then the logical condition that identifies the rows you intend to delete.

In the teams database, suppose we want to delete the Baltimore Ravens (go Browns!) from the NFL table. The code to do that is:

myquery = """

DELETE

FROM nfl

WHERE city = 'Baltimore';

"""

with engine.connect() as conn:

result = conn.execute(text(myquery))

conn.commit()

In this case, city = 'Baltimore' identifies the rows we want to delete in the NFL table. The NFL data now no longer contains a row for the Ravens:

myquery = '''

SELECT *

FROM nfl

'''

pd.read_sql_query(myquery, con=engine)

| city | footballteam | |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | Buffalo | Buffalo Bills |

| 1 | Miami | Miami Dolphins |

| 2 | Boston | New England Patriots |

| 3 | New York | {"New York Jets","New York Giants"} |

| 4 | Cleveland | Cleveland Browns |

| 5 | Cincinnati | Cincinnati Bengals |

| 6 | Pittsburgh | Pittsburgh Steelers |

| 7 | Kansas City | Kansas City Chiefs |

| 8 | Las Vegas | Las Vegas Raiders |

| 9 | Los Angeles | {"L.A. Chargers","L.A. Rams"} |

| 10 | Denver | Denver Broncos |

| 11 | Nashville | Tennessee Titans |

| 12 | Jacksonville | Jacksonville Jaguars |

| 13 | Houston | Houston Texans |

| 14 | Indianapolis | Indianapolis Colts |

| 15 | Philadelphia | Philadelphia Eagles |

| 16 | Dallas | Dallas Cowboys |

| 17 | Washington | Washington Commanders |

| 18 | Atlanta | Atlanta Falcons |

| 19 | Charlotte | Carolina Panthers |

| 20 | Tampa Bay | Tampa Bay Buccaneers |

| 21 | New Orleans | New Orleans Saints |

| 22 | San Francisco | San Francisco 49ers |

| 23 | Phoenix | Arizona Cardinals |

| 24 | Seattle | Seattle Seahawks |

| 25 | Chicago | Chicago Bears |

| 26 | Green Bay | Green Bay Packers |

| 27 | Minneapolis | Minnesota Vikings |

| 28 | Detroit | Detroit Lions |

7.6. Cleaning and Manipulating Data with SQL Read Operations#

After using joins to combine data tables in the database, the data needs to be manipulated to make the data more convenient to use. That might involve narrowing down the data to a specific subset of interest, performing calculations on the data to generate new features, and changing the appearance of the data. In “Tidy Data”, Hadley Wickham defines four essential “verbs” of data manipulation:

Filter: subsetting or removing observations based on some condition.

Transform: adding or modifying variables. These modifications can involve either a single variable (e.g., log-transformation), or multiple variables (e.g., computing density from weight and volume).

Aggregate: collapsing multiple values into a single value (e.g., by summing or taking means).

Sort: changing the order of observations (p. 13).

In addition it may be necessary to pull only a selection of the columns into the output, or to change the names of the columns to more readable and useful ones. These operations can be performed within SQL read commands by using the WHERE clause for filtering, mathematical operators to transform columns, the GROUP BY syntax for aggregation, the ORDER BY, ASC, or DESC clauses for sorting, and the AS keyword for renaming columns.

7.6.1. Example: Wine Reviews#

To illustrate how to issue queries to read data while manipulating and cleaning the data, we will use the PostgreSQL version of the wine review database that we created in module 6. If you want to follow along with these example, follow the instructions in the “Using PostgreSQL” subsection of module 6 to get a local wine database running on your system.

For read operations, we can use the pd.read_sql_query() function. For that, we first have to use sqlalchemy to set up an engine that connects pandas to the database:

dbms = 'postgresql'

package = 'psycopg'

user = 'postgres'

password = pgpassword

host = 'localhost'

port = '5432'

db = 'winedb'

engine = create_engine(f"{dbms}+{package}://{user}:{password}@{host}:{port}/{db}")

The logical ER diagram for the wine reviews database is

7.6.2. Selecting Columns#

SELECT and FROM are the primary SQL verbs for reading data. In many of the examples up to this points, we’ve issued queries like

SELECT *

FROM table;

that pull all of the rows and all of the columns from a single data table. The * character is called a wildcard character. When typed by itself, the wildcard captures all of the columns in a table. But sometimes we are interested in only a selection of the columns. In that case, we replace the wildcard with the columns we want to include in the output. The following syntax includes three columns from a specified data table:

SELECT col1, col2, col3

FROM table;

Suppose that I want to know the title, variety, price, points, country, and reviewer for all of the wines in the data. Title, variety, price, and points are all in the reviews table, country is in the locations table, and the reviewer (taster_name) is in the tasters table. To produce the data I need to join these three tables while also using SELECT to identify only the columns I am interested in. Inner joins are appropriate because every wine in the data has both a location and a reviewer, so no rows should be unmatched.

The best way to select columns across multiple tables is to use aliasing, the same way we did for joins. In this case, if we alias the reviews table as r, locations as l, and tasters as t, we can use these same aliases to inform SQL where to find each column in the SELECT syntax.

The code to return this dataframe is:

myquery="""

SELECT r.title, r.variety, r.price, r.points, l.country, t.taster_name

FROM reviews r

INNER JOIN locations l

ON r.location_id = l.location_id

INNER JOIN tasters t

ON r.taster_id = t.taster_id;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(myquery, con=engine)

| title | variety | price | points | country | taster_name | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Giesen 2011 Clayvin Single Vineyard Selection ... | Pinot Noir | 90.0 | 89 | New Zealand | Joe Czerwinski |

| 1 | Groot Constantia 2012 Pinotage (Constantia) | Pinotage | 20.0 | 89 | South Africa | Lauren Buzzeo |

| 2 | Gualdo del Re 2010 Amansio Passito Aleatico (V... | Aleatico | 55.0 | 89 | Italy | Kerin O’Keefe |

| 3 | Cambridge Road 2011 Pinot Noir (Martinborough) | Pinot Noir | NaN | 89 | New Zealand | Joe Czerwinski |

| 4 | Cappella Sant'Andrea 2013 Vernaccia di San Gi... | Vernaccia | 17.0 | 89 | Italy | Kerin O’Keefe |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 103722 | Barba 2011 I Vasari Old Vines (Montepulciano ... | Montepulciano | 25.0 | 89 | Italy | Kerin O’Keefe |

| 103723 | Flying Dreams 2011 Reserve Tempranillo (Columb... | Tempranillo | 45.0 | 89 | US | Sean P. Sullivan |

| 103724 | Greenhough 2011 Hope Pinot Noir (Nelson) | Pinot Noir | NaN | 89 | New Zealand | Joe Czerwinski |

| 103725 | Hazlitt 1852 Vineyards 2013 Unoaked Chardonnay... | Chardonnay | 16.0 | 89 | US | Anna Lee C. Iijima |

| 103726 | Hollen Family Vineyards 2007 Cabernet Sauvigno... | Cabernet Sauvignon | 15.0 | 89 | Argentina | Michael Schachner |

103727 rows × 6 columns

7.6.3. Logical Statements#

Most programming languages have the capacity to evaluate a statement as being either true or false, or true for some values and false for others. A logical statement uses logical operators that define how values should be compared. In SQL, logical statements are used with the WHERE statement to select the rows to include in the output.

For SQL, logical statements either compare a column to another column, or compare a column to one or more reference values. The following logical operators are available:

=- is equal to?<- is less than?>- is greater than?<=- is less than or equal to?>=- is greater than or equal to?<>- is not equal to?BETWEEN a AND b- true if a value exists within the range from a to b, including a and bIN ('element1','element2','element3')- true if a value is one of the elements in the given setNOT- true if the rest of the logical statement is false, false if the rest of the logical statement is trueAND- links separate logical statements together such that the overall statement is true only when all of the linked statements are trueOR- links separate logical statements together such that the overall statement is true when any of the linked statements are trueLIKE pattern- true if the string value matches the given pattern:LIKE '%%text'captures all rows in which a value in a given column ends with ‘text’LIKE 'text%%'captures all rows in which a value in a given column begins with ‘text’LIKE '%%text%%'captures all rows in which a value in a given column contains ‘text’

()- parts of the logical statement that are contained within parentheses are evaluated first

I will show examples of how to use these logical statements for filtering rows in the next section.

7.6.4. Filtering Rows#

Suppose we wanted to know the title, the variety, and the price of the French wines that Roger Voss scored as 100. It’s a simple semantic sentence, but it connects to a more complicated set of SQL functions. First consider all of the columns we need to use to process the sentence:

title, from the reviews table

variety, from the reviews table

price, from the reviews table

French, a value of country, from the locations table

Roger Voss, a value of taster name, from the tasters table,

and 100, a value of points, from the reviews table.

Because we need to use data from the reviews, locations, and tasters tables, we need to inner join reviews, locations, and tasters.

But then on top of this join, we need to restrict both the columns and rows. We only want title, variety, and price in the final data, so we use SELECT to keep only these columns.

To restrict the rows, we use WHERE along with a logical condition. This logical condition has a few parts: we want wines in which country='France', taster_name='Roger Voss', and points=100. All three conditions need to be true for us to want to keep the row, so we connect the three statements with AND.

The SQL query that returns the title, the variety, and the price of the French wines that Roger Voss scored as 100 is:

myquery = """

SELECT r.title, r.variety, r.price

FROM reviews r

INNER JOIN locations l

ON r.location_id = l.location_id

INNER JOIN tasters t

ON r.taster_id = t.taster_id

WHERE l.country='France' AND t.taster_name='Roger Voss' AND r.points=100;

"""

pd.read_sql_query(myquery, con=engine)

| title | variety | price | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Krug 2002 Brut (Champagne) | Champagne Blend | 259.0 |

| 1 | Château Léoville Barton 2010 Saint-Julien | Bordeaux-style Red Blend | 150.0 |

| 2 | Louis Roederer 2008 Cristal Vintage Brut (Cha... | Champagne Blend | 250.0 |